Natural Doesn’t Mean Safe: The Myth of Essential Oil Purity

If it grew in the ground, it must be safe. Many consumers surprisingly find themselves agreeing with that sentiment. But does it hold any truth?

THE SCENT DAILY

6/20/20255 min read

The Comfort of a Natural World

“If it grew in the ground, it must be safe.”

Walk down the wellness aisle and this story is everywhere: tiny amber bottles whispering pure, therapeutic-grade, Mother-Nature-approved. Marketing copy leans on this all too familiar pastoral shorthand—rolling lavender fields, cedarwood forests, orange groves at sunrise—to assure us that what comes from the soil cannot possibly betray us. Such branding has built us a liking for the word “natural”. The subtext here is potent: pharmaceuticals are the province of laboratories and risk; nature is the domain of gardens and safety.

Yet, the truth is that this contextual vocabulary of “natural” is merely emotional, not chemical. Chemists who actually map these liquids know that every milliliter of lavender oil carries more than 100 distinct molecules, some useful, others indifferent, a handful potentially harmful in the wrong dose. The plant cares nothing for our human categories of “gentle” and “harsh”; it manufactures compounds to ward off insects, bacteria, and grazing animals. When we distill those compounds at industrial scale, we inherit both the fragrance and the plant’s biochemical arsenal. “Natural” therefore tells us nothing about biological effect—only about source. The truth hides in plain sight: a source can be natural, yet its molecules can be bioactive, allergenic, even neurotoxic.

The Chemistry Knows No Garden Gates

Fundamentally, we must understand that essential oils are NOT “single-ingredient” extracts. Retail labels rarely mention more than the headline constituent—“100 % Melaleuca alternifolia” or “100 % Eucalyptus globulus.” That shorthand tempts buyers to imagine a neat, uniform substance, as if tea-tree oil were analogous to distilled water.

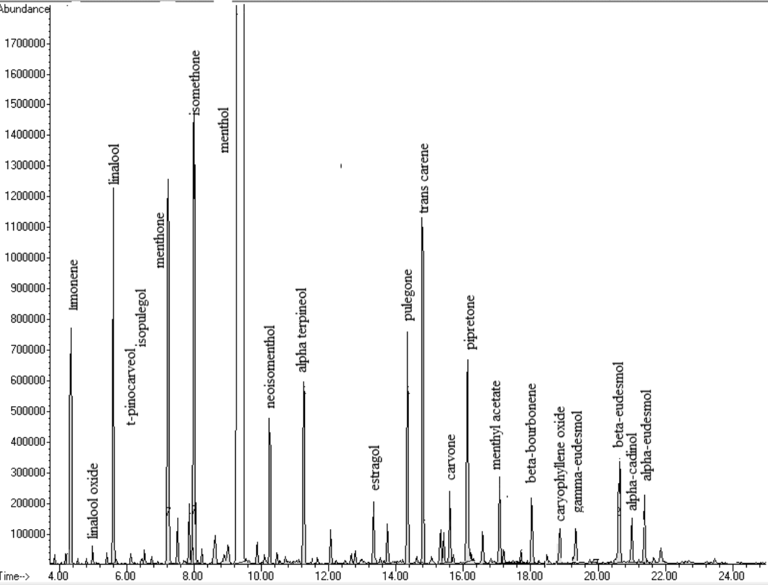

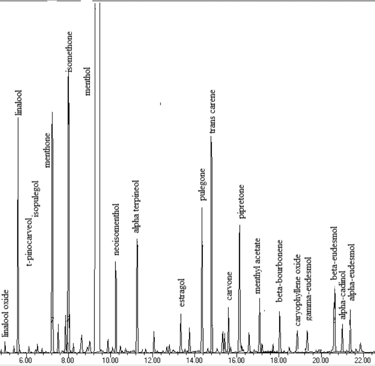

A gas-chromatograph trace shows a skyline of peaks: terpinen-4-ol, α-terpineol, cineole, limonene, dozens more. Some peaks make tea-tree a bright antiseptic; others oxidize in open air into skin-sensitizing aldehydes. Adulteration adds still more players: synthetic linalool to boost aroma, phthalates to stretch yield, even petrochemical solvents slipped in to cut viscosity. Purity claims often ignore this complexity because purity is expensive to verify and easy to fake. In blind-sample audits, up to one-third of “100 % pure” oils fail isotope-ratio tests, revealing cheaper synthetic fillers disguised by fancy labels.

GC-MS of an essential oil. Source

When the Poison-Control Lines Light Up

Influencer reels show peppermint foot rubs, oregano “immunity bombs,” lemon water “detoxes.” Adverse events? “Maybe if you’re allergic,” the captions shrug.

In 2022 alone, U.S. poison-control centers logged more than 2,200 tea-tree oil exposures—twice the call volume of any other named oil—and over 10 % required treatment in healthcare facilities. Australian data echo the trend: eucalyptus and clove oils rank among the leading causes of childhood hospitalization for household poisoning, with severe toxicity sometimes triggered by as little as 5 mL of ingestion.

Clinical literature documents seizure-grade neurologic events from excessive eucalyptus inhalation, liver injury linked to repeated pennyroyal ingestion, and fatal outcomes when wintergreen oil (98 % methyl salicylate) is mistaken for peppermint and swallowed neat. The incidents do not cluster around fringe users; they occur in ordinary kitchens, yoga studios, and day-care centers where the line between aromatherapy and folk medicine blurs.

And what links these events isn’t just chemistry, but it’s marketing. Often, each bottle arrived under the halo of “natural,” a word that somehow anesthetizes skepticism in buyers. Consumers handle these oils as if their botanical origins exempts them from toxicology. The reassurance by rustic labels and friendly influencer endorsements does not help either. But we must face the truth that molecules act independently of our narratives. Whether an oil is pressed from leaves or synthesized in a lab, its effects are real, and doses—not origin—determine the danger. In most cases above, the myth that “natural = safe” left users unprepared for the consequences of potency.

Below is an interactive display of some of the most common labels and what they indicate.

Purity as a Moving Target

Many essential oil brands today claim that they are “therapeutic grade”. This may sound clinical and official, but it has no standardized definition. Neither the U.S. FDA nor most international regulators recognize or enforce the term. In reality, it’s a marketing phrase, not a certification. Yet, companies use it to imply a high level of safety and quality. And they do it by promoting their own internal or third-party testing systems—proprietary protocols with names like “four-sense” evaluations that rely on sight, smell, feel, and chromatography. These are presented as proof of purity, an attempt to reinforce the idea to the consumer that every drop is pristine. But without regulatory benchmarks or consistent oversight, such claims are largely self-governed, and just as often self-serving.

In the United States, essential oils fall into a regulatory gray zone: they can be food, cosmetic, or drug depending on marketing claims, yet none of those categories mandates premarket safety data if the product avoids explicit therapeutic promises.

The consequence is predictable: what “passes” today can be hazardous tomorrow. Fresh citrus oils may be benign, but photo-oxidation under store lights spawns reactive furocoumarins that supercharge UV sensitivity. Similarly, iron-contaminated lavender oxidizes into sensitizers within weeks of opening. Batch sheets rarely reveal these temporal changes, leaving consumers to navigate purity on an honor system that chemistry refuses to respect. But consumers do have something on their side. Products that are harmful to the consumer under certain conditions are often immediately removed under the threats of lawsuits and reputation damage. This is why large companies in the industry are essentially forced to take as much care as they possibly can for their products. The same however cannot be said about smaller local businesses who have less to lose.

Does this mean you should blindly trust only the industry giants when buying essential oils? Not exactly—but it does mean you should stay alert. Big companies, for all their flaws, face real pressure: lawsuits, recalls, and the ever-present threat of public backlash force them to take precautions that many smaller sellers can afford to ignore. Marketing language like “pure,” “organic,” or “therapeutic grade” can lull you into a false sense of security. Nature has always made potent chemistry that’s not just for healing, but for defense. It’s your job, as a consumer, to look past the pastoral packaging and ask better questions.

The Regulatory Patchwork and the Myth of Uniform Safety

Many users assume a silent guardian—FDA in the U.S., TGA in Australia, EFSA in Europe—quietly policing every sale. But it cannot be guaranteed as oversight is most times fragmented and too often then not, reactive.

U.S. regulators intervene mainly after harm occurs, relying on post-market surveillance and company self-reporting. The European Union’s Cosmetics Regulation limits certain allergenic constituents, yet importers can relabel a cosmetic oil as a “household fragrance” to bypass the stricter thresholds. Countries such as India and Brazil mandate ISO standards on paper, but enforcement budgets struggle against explosive e-commerce growth. The net effect: the same bottle of ylang-ylang may sail through customs in one jurisdiction while being detained in another for benzyl benzoate exceedance. Consumers read a global internet but buy into a local legal vacuum.

Toward a Risk-Literate Aromatherapy Culture

The mission is not to villainize essential oils but to mature our relationship with them. Safety begins by discarding the reflexive equation of “natural” with “harmless.” Read GC-MS reports the way you read nutrition labels; demand batch numbers and bottling dates; store oils cool and capped; dilute correctly; question dramatic internal-use protocols that leapfrog professional toxicology. Advocate for harmonized regulations that treat these potent liquids with the same respect we grant over-the-counter drugs.

If lavender’s scent helps you sleep, wonderful—inhale via a diffuser at 0.5 % concentration and keep the bottle high above a child’s reach. If peppermint lifts a migraine, terrific—blend one drop in a teaspoon of carrier and patch-test first. But remember: plants fight for survival with the same chemistry that we use for scents. So must we safeguard our wellness with knowledge. We must agree that being natural is only a starting point, not a safety guarantee, and that purity is not necessarily always the goal.