Should you buy or make your own DIY essential oils?

The age-old question. Many online say that you should go for DIY. But is that really always true? Everything comes with its pros and cons. In this article, we dive deeper on what exactly you should know before trying out your own blend of DIY oils, and why, in some cases, going commercial may be the better option for you.

THE SCENT DAILY

6/4/20254 min read

Up-Front Cost vs. Long-Term Spend

DIY

Starter math looks brutal. A decent 10-ml bottle of lavender runs $12–15; add peppermint, frankincense, a couple of carrier oils, and small amber bottles and you’re suddenly out $80 before a single blend hits your diffuser. The consolation prize is longevity: a 10-ml bottle can supply roughly 200 drops. If you rotate three to five oils regularly, that initial haul can last six months or more. Bulk carrier oils (sweet almond, jojoba) drop the per-blend cost even further.

Store-bought

A ready-made 10-ml sleep blend might cost $22. Skeptics love to point out you’re paying for dilution, marketing, and fancy labels. True—but you’re also skipping the box-full of droppers, beakers, and spreadsheet tabs. If you only diffuse at night or roll oil on your wrists before exams, one bottle every two months might be cheaper than a “collector” habit you’ll very likely never finish.

Safety Issues

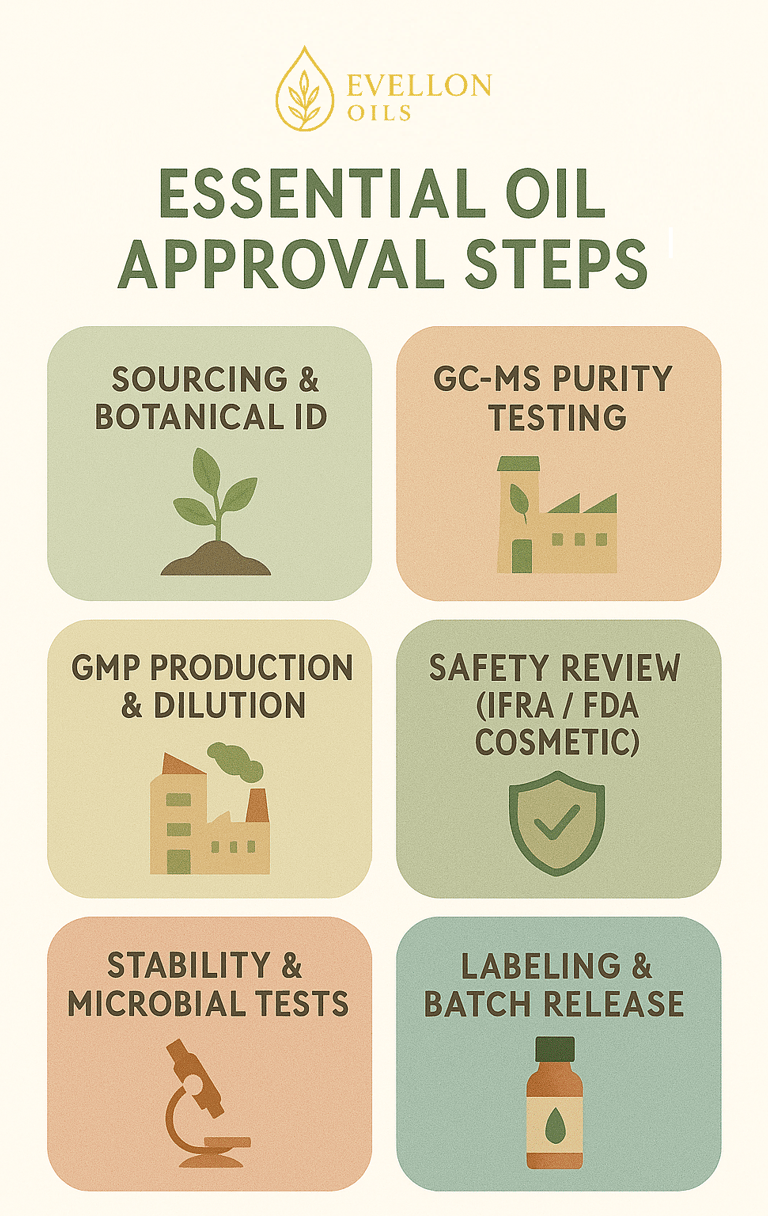

Reputable brands in the U.S. follow cosmetic GMP (Good Manufacturing Practice) and FDA labeling rules: Latin plant name, batch code, net contents, and skin-safe directions. Larger houses also conform to IFRA (International Fragrance Association) limits—e.g., bergamot must stay below 0.4 % in leave-on products to avoid phototoxic burns. Before a “Sleep Roller” hits shelves, it passes stability tests, microbial checks, and a toxicologist’s review. Not fool-proof, but at least someone with a lab coat and liability insurance has run the numbers.

At home you are R&D, quality control, and legal department. No law forces you to log batch numbers or check IFRA tables, yet the chemistry doesn’t care who’s blending. Best practice means:

Dilution math: keep everyday body oils at 1 % (6 drops EO / 30 mL carrier).

Patch tests: 24 h on the inner arm before full use.

Allergen tracking: note each oil’s CAS number and main constituents; oxidized limonene is a top contact allergen.

Phototoxic watch: expressed citrus oils must stay under 0.5 % in any formula exposed to sunlight.

Container hygiene: sterilize bottles with 70 % isopropyl, air-dry, and label “Made: MM/YY; Expire: +12 mo.'

Sourcing single oils from ethical distillers means reading harvest notes. You’re going to have to compare GC–MS charts, choose between Bulgarian and French lavender, and research whether Ethiopian frankincense is worth the extra $4. The upside: full transparency, no mystery fillers. The downside: analysis paralysis.

Retail blends live on brand trust. Some companies test each batch five times; others re-label bulk oil from a drum with a new Instagram-friendly font and sell it for a much higher price. Rule of thumb: if lab results aren’t one click away, click to a different seller.

Shelf Life Comparison

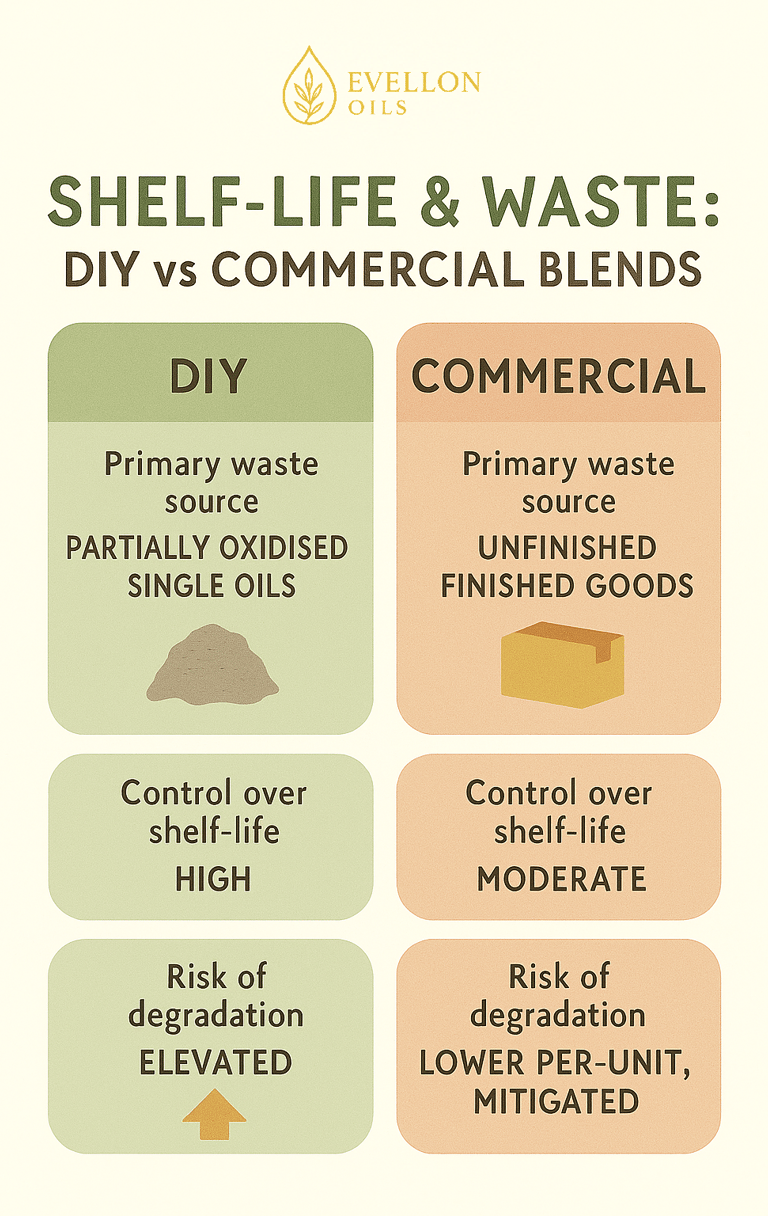

Essential oils are volatile; they oxidize faster than people think. Citrus tops often degrade within 12–18 months, while wood and resin oils soldier on for up to eight years. When you DIY, the clock starts ticking on every bottle you open. When making your own blends, it is very likely that the amount of time your recipe is exposed to oxygen is much higher than the store-bought counterpart.

It's not just that. Despite your DIY blend risking greater oxidation, it also likely does not come with antioxidants in them (unless you go out of your way to add them, but this is unlikely as it involves a more advanced understanding of blend making and is probably too much for a DIY project). Commercial blends usually open one bottle per need (less oxygen exposure), and often have many added antioxidant carriers (vitamin E, fractionated coconut) that slow rancidity. Some even nitrogen-flush bottles before sealing. However, you’re stuck with the company’s ratios, and if you don’t vibe with the scent, that $25 roller could live out its life span in a drawer—whole product wasted instead of small amounts of several oils with different scents that your could have made DIY.

Bottom line is that DIY risks ingredient waste; store-bought risks product waste. Whichever lane you drive, date-label everything, store bottles cool and dark, and treat essential oils like fresh pantry—use them while they’re fresh, not when they’ve faded.

Wrap Up: Commercial or DIY?

In my experience, after a year of systematic use, I have settled on a balanced approach. I prepare a small batch of my own focus blend because adjusting the rosemary-peppermint ratio lets me fine-tune aroma and concentration. For nighttime routines, I rely on a vetted commercial sleep roller; precision matters when dilution must be exact and time is limited. In practice, neither option is inherently superior. The decision depends on usage frequency, desired control, and your available resources.

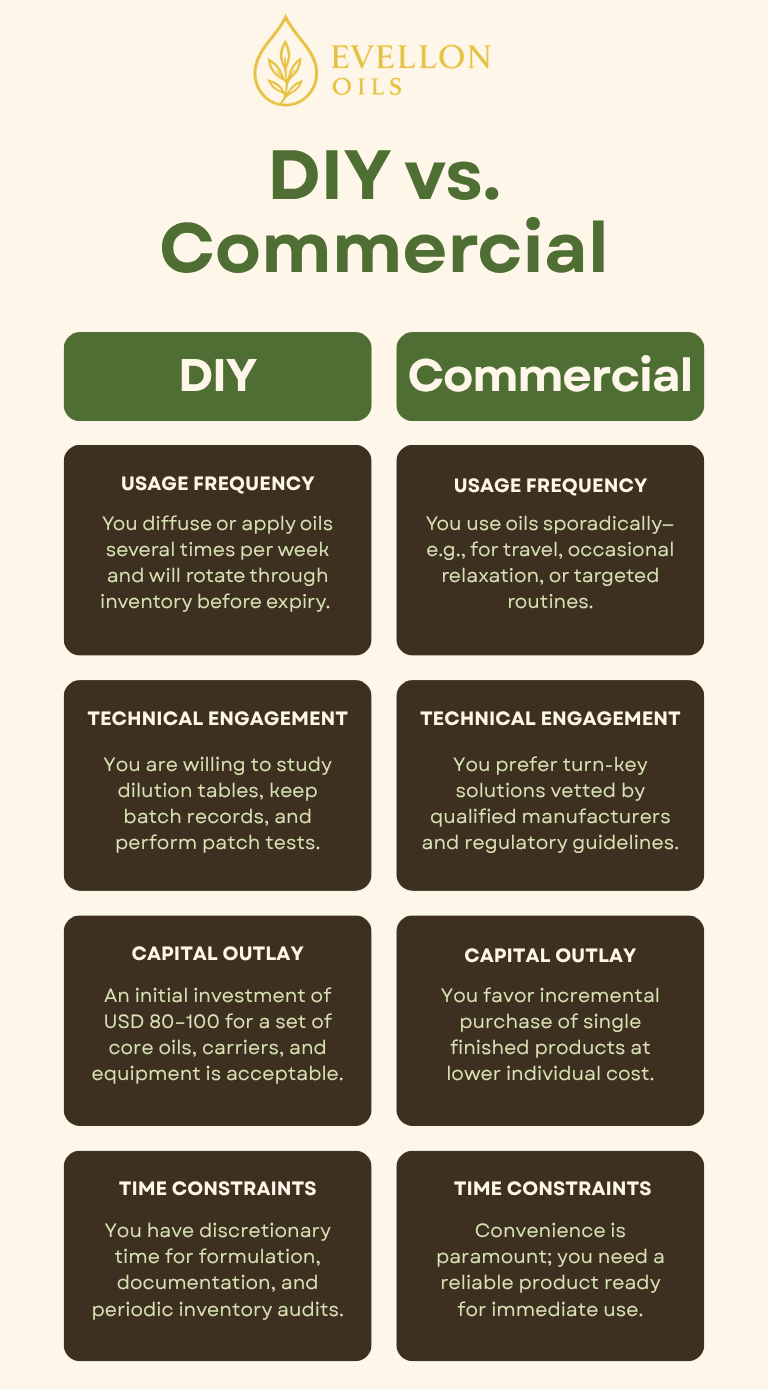

The below infographic briefly summarizes what you should know about approaching essential oils via DIY or buying through commercial means. Ultimately, it really comes down to your preferences and what you want from your oils. To me, I would say that this process is also, in whole, a part of aromatherapy.