The Fragrance Wheel Explained

Breaks down Michael Edwards’ iconic scent classification system—how it organizes fragrance families and helps users find their preferences.

THE SCENT DAILY

7/27/20256 min read

Set a foot inside a perfume shop and you are met with shimmering glass flacons that promise romance, adventure, serenity, or power. Yet unless you happen to be a trained perfumer, these promises blur together into a haze of alcohol and artistry. Forty‑two years ago Michael Edwards noticed that even seasoned sales associates could not reliably guide customers beyond a few familiar blockbusters. His solution was disarmingly modest: a circular diagram that grouped scents according to their dominant olfactory themes. Within a decade the Fragrance Wheel had slipped behind almost every beauty counter, giving both novices and aficionados a shared vocabulary. The wheel is relatively easy to comprehend, but understanding its making can give you a lot of insights into how fragrance design works. It really is helpful in moving you from that casual browser into someone who knows exactly what they want in a scent.

A Short History of Michael Edwards’ Wheel

Michael Edwards, 2014

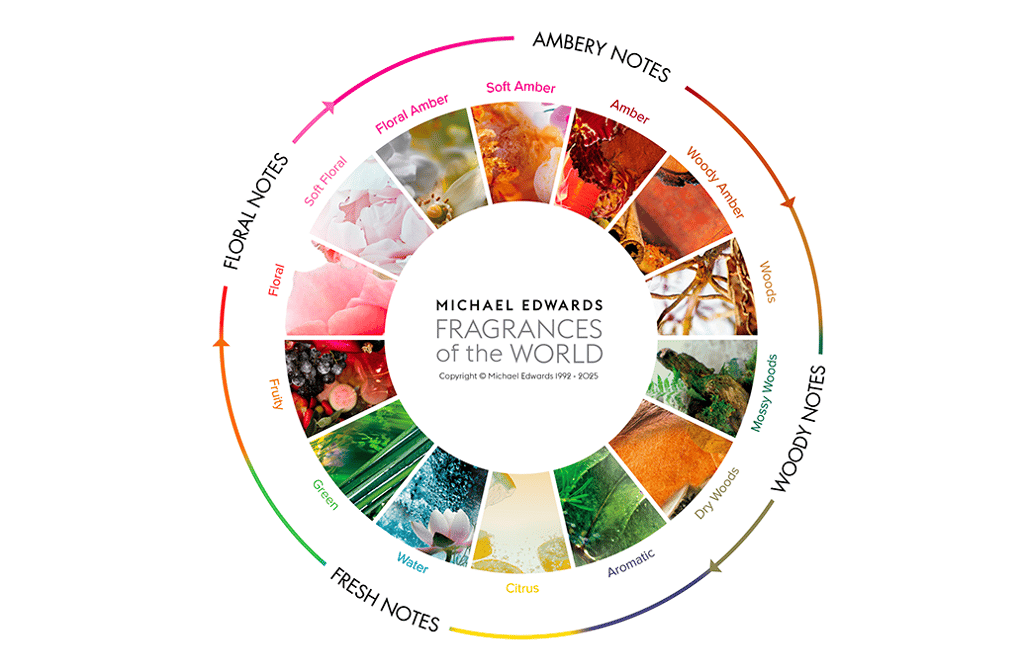

Edwards began as a marketing consultant in the early 1980s, hired by large retailers who wanted to decode fast‑changing perfume trends. While cataloguing hundreds of launches he realized that fragrances tended to cluster around recurring themes: some shimmered like citrus groves, others smoldered like incense‑laden temples, and many drifted somewhere between. To visualize those clusters he drew a circle divided into four quadrants—Floral, Oriental, Woody, and Fresh—then scattered fourteen smaller wedges around the rim to accommodate nuanced hybrids. The idea felt intuitive to shoppers because neighboring categories literally overlapped: if you sat on the edge of Floral and Oriental, your fragrance likely combined roses with vanilla and spice.

From the outset the wheel was a living taxonomy. In the 1990s the Belgian school of minimalist perfumery ushered in sheer aquatic molecules such as calone, prompting Edwards to expand the Fresh quadrant. In 2008 he replaced the term Oriental with Amber after listening to perfumers from the Middle East and South Asia, who pointed out that the old label was both culturally reductive and chemically imprecise. Today the database behind the graphic tracks more than thirty‑five thousand commercial releases and is updated weekly by a small team who spend their days sniffing, analyzing, and arguing about where a new oud‑laced gourmand truly belongs

Mapping the Wheel: Four Quadrants, Two Axes

Picture the wheel like a compass. The north–south axis runs from the airy sparkle of Fresh to the molten warmth of Amber; the east–west axis stretches from petal‑soft Floral to bark‑rich Woody. Moving clockwise around the rim produces a gradual shift rather than abrupt jumps; the citrus zing of a summer cologne fades into aquatic breezes, which in turn drift toward herb‑drenched greens before blooming into garden flowers. Turn further and you meet blossoms infused with spice and vanilla, then resinous ambers that darken into smoky woods, until finally the circle closes with crisp, cedar‑laden compositions that lift you back toward citrus brightness again.

The genius of the design is that it reflects how our noses actually perceive scent. Humans register odors as overlapping patterns of molecules, not as rigid categories. By allowing each wedge to blur into its neighbors, the wheel encourages discovery while acknowledging nuance. Stand at any point along the rim and you can see—in a single glance—which direction will lead you to something lighter, sweeter, woodier, or fresher.

The Families in Depth: From Petals to Smoke

Rather than list every sub‑family, we’ll look at the four great regions and linger long enough to catch their moods, raw materials, and celebrated examples.

Floral compositions, which still account for roughly a third of annual launches, centre on natural or reconstructed flower accords. A classic bouquet such as Dior J’Adore radiates jasmine, rose, and ylang‑ylang in a harmony. Push the dial slightly clockwise and aldehydic molecules introduce a fizzy champagne note that turns petals into silk—think Chanel No. 5 or Estée Lauder White Linen. Drift the other way and vanilla, clove, or benzoin wrap the bouquet in candlelit warmth, giving rise to modern sensual florals like Yves Saint Laurent Black Opium. Patrons who claim they “are not floral people” often discover that what bothers them is not the flower itself but how it is framed; swap soap‑powder aldehydes for a squeeze of bergamot and suddenly the same rose feels fresh from the garden.

Amber perfumes (the quadrant formerly labelled Oriental) gather around a resin‑vanilla axis that conjures velvet drapes, gilded lanterns, and slow‑burning incense. The grand dame Guerlain Shalimar opens with bright citrus before plunging into smoky vanilla and labdanum, a template countless perfumers still quote. Contemporary ambers often tame the sweetness with iris, saffron, or leather; Prada Infusion d’Iris floats its powdery heart atop transparent musks, while Tom Ford Oud Wood deepens the accord with agarwood and pepper until it feels like a desert campfire. Wearers sometimes wonder if amber scents are season‑bound. The answer lies in concentration and placement: a single spritz on clothing in humid weather can feel as comforting as a cashmere scarf in January.

Woody fragrances ground the wheel with trunks, roots, and polished timber. Sandalwood, cedar, and vetiver are the holy trinity here, each lending its own texture: sandalwood is creamy and slightly sweet, cedar is pencil‑sharp and dry, and vetiver is grassy smoke. In Le Labo Santal 33, sandalwood mingles with papyrus and leather, creating an androgynous aura that really brings out both an artist’s loft and a campfire after rain. Oakmoss and patchouli pull the dial into mossy woods reminiscent of damp forest floors; birch tar and smoke steer it toward the crackle of dry twigs. For many consumers these scents feel “masculine” because marketing departments have spent decades printing them on men’s flankers, yet on skin they can read as quietly confident on anyone who enjoys subtlety over sweetness.

Fresh compositions live at the top of the wheel, where volatility and clarity reign. Citrus oils—bergamot, lemon, grapefruit—dominate the opening moments, often uplifted by pepper or ginger and anchored by soft musk. If citrus is sunrise, aquatic molecules like calone are a salt‑sprayed breeze that flies in around midday, as immortalized in Giorgio Armani Acqua di Giò. Green facets made from galbanum, basil, or violet leaf raise visions of crushed herb gardens; fruity notes borrow the dew of apples or pears to add a picnic‑blanket casualness. The lighter molecular weight of these ingredients means they disperse quickly, so fresh fragrances are perfect for situations that require subtlety: offices, hot climates, or gym bags. A small refrigerated travel spray can reset the mind better than an espresso.

Applying the Wheel: From Boutique Counter to Bedroom Vanity

Knowing where your current favorite perfume sits on the wheel instantly suggests intelligent next steps. Suppose you adore Chanel Chance Eau Tendre, a fruity‑floral perched near the border of Fresh and Floral. Slide clockwise into the green wedge and you might sample Hermès Un Jardin sur le Nil; slip the other way toward light ambers and Maison Francis Kurkdjian Baccarat Rouge 540 could feel like a gilded evening gown stitched from a daylight dress.

Retailers exploit these neighborly relationships when designing store layouts. A circular tester table organized by quadrant invites customers to wander organically rather than zig‑zag across alphabetical shelves. Sales staff—trained to ask “citrus bright or creamy floral?” instead of “for him or for her?”—report higher conversion rates because the conversation revolves around olfactive desire rather than gender stereotypes.

Perfumers, meanwhile, treat the wheel as a sketchbook. A client brief that specifies “modern Amber with a fresh opening” translates into a composition that begins in the citrus arc, swings through transparent florals, and lands softly in vanilla‑resin territory. Because raw materials carry cost implications, the wheel even influences budgeting: heavy sandalwood or natural iris notes push formulas into luxury price brackets, whereas synthetic musks keep them within mass‑market margins.

For personal use the most practical strategy is to build a mini‑wardrobe anchored on different quadrants. One scent might function as a freshly ironed white shirt, another as a velvet dinner jacket, while a third becomes the olfactory equivalent of hiking boots. Rotating families prevents nose fatigue—the gradual desensitization to a favorite perfume—and reflects shifting seasons, moods, and social settings.

Myths, Questions, and Course Corrections

The wheel’s simplicity occasionally invites misconceptions. Some newcomers assume the graphic is prescriptive, a kind of scented caste system that locks perfumes in place. In reality many formulas straddle borders or drift with reformulations; an Eau de Parfum may occupy the woody edge of Amber, while its lighter Eau de Toilette sibling breezes into Floral territory. Others worry that amber scents are inherently sweet or that fresh ones lack longevity. Both notions dissolve once you sample modern interpretations: isobutyl quinoline can make an amber bone‑dry, while high‑tech musks allow an eau fraîche to linger through a long‑haul flight.

Another frequent question concerns cultural preference. Why do Gulf region shelves groan under oud‑heavy bottles while Japanese counters glow with delicate tea accords? Geography, climate, and social customs influence projection expectations; the wheel accommodates these preferences without value judgement. Its true proposition is inclusivity: wherever you begin, there is always a path toward something new yet relatable.

Final Thoughts

Michael Edwards did not invent perfume families, but he did arrange them into a map anyone can read. In doing so he turned perfume shopping from a guessing game into an act of informed curiosity. The wheel will continue to evolve—perhaps a dedicated gourmand quadrant will one day earn its own slice—but its core promise endures: place any bottle at one point on the rim and you instantly know where to explore next. After all, fragrance is the most portable form of memory; the right one should feel less like a product and more like a story that you carry on your skin.