What is Aromatherapy? Is it all a big fuss?

Part history lesson, part myth-busting deep dive. Here, we attempt to unpack the science, hype, safety tips, and real-world uses of essential oils so you can tell placebo from proven perks and decide whether aromatherapy deserves a spot in your self-care toolkit.

THE SCENT DAILY

6/2/20255 min read

Aromatherapy in a Nutshell

At its simplest, aromatherapy is the use of concentrated plant extracts—essential oils—for therapeutic purposes. “Therapeutic” is the slippery word here. Some people mean it literally (measurable physiological effect), others mean it figuratively (it smells nice and helps me chill). The practice usually involves:

Inhalation: diffusers, steam bowls, or just a dab on the wrist.

Topical application – diluted in a carrier oil for massage or skincare.

Very rarely ingestion – highly controversial; most professionals advise against it unless you’re working with a qualified clinical aromatherapist.

A Quick History

The impulse to bottle a mood in scent predates alphabets. Temple reliefs at Edfu, carved around 3 500 BCE, show Egyptian priests heating kyphi—an 18-ingredient resin cake—to cleanse the air and “feed” the gods. Myrrh, frankincense, and cedarwood oil soon travelled east on camel caravans, valued as embalming agents, wound salves, and diplomatic gifts. Ayurvedic treatises from the Vedic era describe sandalwood paste cooling feverish skin, while China’s first pharmacopeia, the Shennong Ben Cao Jing (1st century CE), lists cassia bark, star anise, and camphor for toothache and battlefield morale.

Steam—and politics—changed the game. In the 10th century Persian polymath Ibn Sīnā (Avicenna) perfected steam distillation, separating rose oil so potent that a single drop perfumed an entire silk robe. His techniques reached crusader Europe, where monastic infirmaries in Salerno and Montpellier stocked lavender, rosemary, and juniper extracts. When the Black Death swept the continent, plague-doctor beak masks were stuffed with cloves and cinnamon in a last-ditch nod to the miasma theory. Renaissance apothecaries in Venice distilled bergamot and neroli for courtly handkerchiefs, and by 1600 the Dutch East India Company was shipping ylang-ylang from the Moluccas to Amsterdam.

Modern aromatherapy began with a lab mishap. In 1910 French chemist René-Maurice Gattefossé reportedly plunged a burned hand into lavender oil and, impressed by the healing, devoted his career to essential-oil chemistry, coining “aromathérapie” in 1937. His disciple, army surgeon Jean Valnet, used thyme and clove dressings on war wounds when antibiotics were scarce. The movement reached Britain through Marguerite Maury, who combined oils with massage in the 1950s, and exploded in 1970s California spas. By the 1990s hospital wards in France and Japan were diffusing citrus oils to calm patients. Today researchers dissect molecules with GC-MS and run trials, showing the story keeps evolving every year.

Shennong Ben Cao Jing (1st century CE)

How Essential Oils are Made

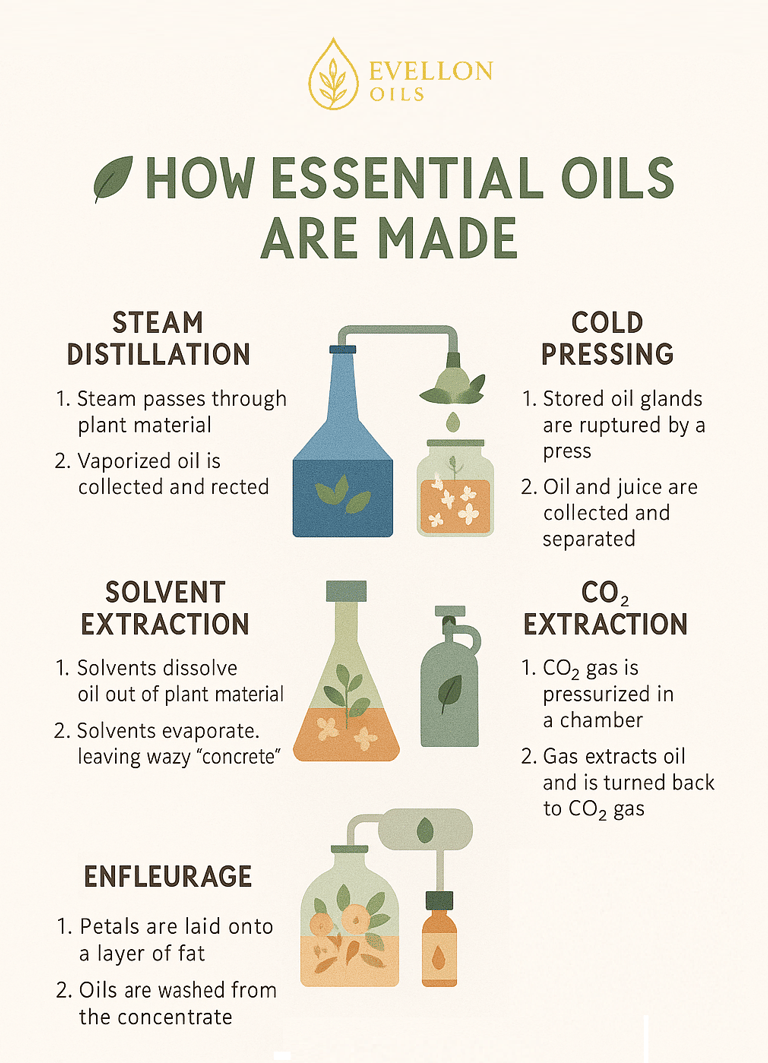

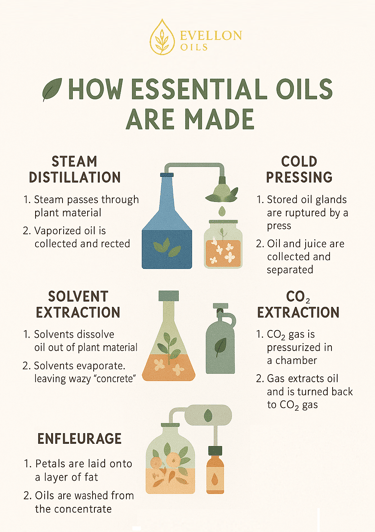

Steam distillation is still the main means of production in the essential-oil world, and it’s deceptively low-tech. Fresh plant matter is packed into a sealed column; pressurized steam rises through the biomass, rupturing oil glands and carrying volatile molecules upward as vapor. That vapor hits a condenser coil, cools, and separates into two layers: a thin, floating film of essential oil and the aromatic hydrosol (floral water) beneath. A 50-litre alembic loaded with peppermint leaves might yield barely 300 mL of oil, so you start to see why the good stuff isn’t cheap.

Not every plant tolerates that much heat. Fragile jasmine and rose often become absolutes through solvent extraction. Petals bathe in food-grade hexane or ethanol, which dissolves waxes and scent molecules into a waxy “concrete.” A second alcohol wash removes the wax, leaving a thick, intensely perfumed liquid. While solvent residues are stripped out, some purists prefer supercritical CO₂ extraction: carbon dioxide is pressurized until it behaves like a solvent, then vented off with no residue, preserving more delicate aromatics and color compounds.

Citrus oils skip heat and chemistry altogether with cold pressing. Industrial rollers studded with metal teeth grate and squeeze rinds, releasing a bright cocktail of limonene and citral. Because this process captures everything—pesticides included—organic peel is non-negotiable if the oil will touch skin.

The final method is enfleurage, now largely artisanal. Fresh petals are pressed into layers of odorless animal fat that absorb their fragrance over 24 hours; spent petals are swapped repeatedly until the fat is saturated. The result is washed with alcohol to yield a rare enfleurage extract. Labor-intensive and costly, it survives mainly in boutique perfumery.

Some of the Science

Essential oils are a mixture of volatile organic compounds. A single oil can contain dozens, sometimes hundreds, of molecules—terpenes, aldehydes, phenols—each with its own signaling potential in the body. For example:

Linalool (lavender, coriander) – has been shown to modulate the GABAergic system, producing sedative effects in animal studies.

1,8-Cineole (eucalyptus) – acts as a mucolytic, thinning mucus and easing breathing.

Menthol (peppermint) – binds to cold receptors (TRPM8), tricking nerves into feeling a cooling sensation.

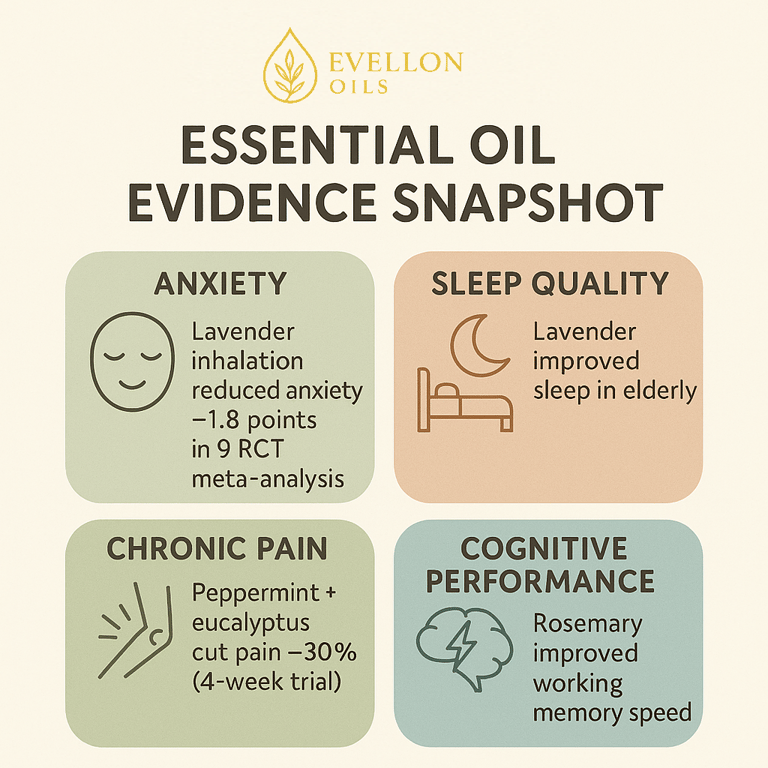

But concentration matters. Most studies that demonstrate measurable effects use controlled doses—often higher or more refined than your plug-in diffuser emits. We have summarized the findings of the potential benefits below.

Critics argue benefits stem largely from expectation: if you believe lavender relaxes you, your breathing slows, cortisol drops, heart rate follows—and voilà, relaxation. Functionally, does it matter? When my headache eases, I rarely stop to ask whether it was the menthol’s molecular action that caused it. If the ritual is safe, inexpensive, and subjectively helpful, many folks consider that a win. Science can—and should—keep teasing apart mechanisms, but lived experience is still data, just messier.

In truth, aromatherapy’s credibility suffers mainly because marketing got ahead of evidence. When a single MLM webinar claims oregano oil cures the flu, the entire field takes a reputational hit. Combine that with green-washed buzzwords—“toxins,” “chemical-free,” “frequency”—and skeptics (rightly) cringe.

Yet, beneath the noise, legitimate clinical aromatherapy exists. Hospitals in France and Japan diffuse certain oils in wards to reduce airborne pathogens or patient anxiety. German midwives often use clary sage during labor to encourage uterine contractions. Regulation is stricter there; oils are treated as herbal medicines, not lifestyle add-ons. The U.S. market, by contrast, is the wild west.

So...Is It All a Big Fuss?

If “fuss” means overpriced starter kits and miracle claims—sure, those deserve side-eye.

If “fuss” means the idea that aroma can nudge mood, pain perception, or sleep—the evidence leans yes, at least modestly.

If “fuss” means you must rebuild your life around essential oils—hard no.

Here’s my litmus test:

Cost – A $15 bottle that lasts six months and maybe shaves the edge off stress? Worth it.

Compatibility – Integrates into things I’m already doing (studying, stretching, winding down)? Double win.

Risk – Low if I dilute and respect contraindications.

For me, aromatherapy sits in a pragmatic middle ground: more than just a pleasant smell, less than a panacea. I treat it like a coffee in the morning—enhances routine, provides small measurable perks, but life will go on if it runs out.